Utopian Scholastic: A Consumer Aesthetic of Intellectual Curiosity and Optimism

- Matthias Castle

- Sep 15, 2025

- 20 min read

Utopian Scholastic was a short-lived but extraordinary consumer aesthetic of the 1990s. At its core, it was about turning knowledge itself into something wondrous. Brightly colored encyclopedias, multimedia CD-ROMs like Microsoft Encarta, and PC games like Myst – invited children and young adults to imagine that learning was not just useful, but magical – a gateway to a better future. Historically, it emerged in the 1980s as a unified visual movement adopted by mainstream culture. The aesthetic surged to prominence in the 1990s and declined by the early 2000s. It was rediscovered by Suze Huldt and Karl Kraft in 2017, leading to its revival since 2019. The aesthetic is an art design language which clearly communicates a sense of wonder and intellectual curiosity about scholastic knowledge with an optimistic view about the future. The aesthetic was primarily aimed at children and young adults through many platforms, visually communicated through a variety of mediums - print, digital software (including early computer-generated imagery (CGI), 3D models, and virtual reality), film, television, games, and more. The term Utopian Scholastic was coined by Suze Huldt and Karl Kraft through the Facebook group called “Utopian Scholastic Designs from a pre-9/11 World” (utopian scholastic designs from a pre-9/11 world | Facebook). The Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute (CARI) researcher Evan Collins has collected artifacts of the aesthetic online at Utopian Scholastic | Are.na. The CARI website gives a brief description and gallery of the aesthetic (CARI | Aesthetic | Utopian Scholastic). A consumer aesthetic stands in contrast to Internet aesthetics such as Dark Academia and Cottagecore.

In this article, I explore the five major components of the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic: (1) visual content, (2) design principles, (3) pedagogical roots, (4) cultural context, and (5) its decline and revival. I study why it looks the way it does and tracing its pedagogical roots, which are surprising and illuminating for those who only look at its surface. Going deeper, I discovered its roots are the classical art of memory, a mnemonic system of techniques for remembering large amounts of information, and, even more surprisingly, the aesthetic has a philosophical and spiritual foundation in Neoplatonism, a version of Platonic philosophy that adheres to the doctrine that all of reality originates from a single principle, “the One”. The optimistic attitude of Utopian Scholastic emerges from the confluence of the cultural forces which constituted the zenith of its 1990s zeitgeist. Lastly, I examine its decline as an aesthetic. In the midst of the aesthetic’s rediscovery and revival, those who are attracted to its beautiful, harmonious, and nostalgic themes find themselves asking a recurring question which is “What defines Utopian Scholastic?”

Visual Content

The visual content of Utopian Scholastic centers around educational knowledge of the natural sciences, the humanities, social sciences, and mathematics. For the natural and social sciences, the signature visuals included solar system charts, dinosaurs, crystals, plants, clouds, and human anatomy illustrations. For the humanities, the signature visuals included such things as Ancient Egypt’s King Tut and the pyramids, Ancient Greek statues, medieval knights, and musical notations. For mathematics, the visual content usually includes a variety of architectural features, geometric symmetry, proportion, and shapes. More generally, Utopian Scholastic design included school supplies like books, rulers, globes, and pencils.

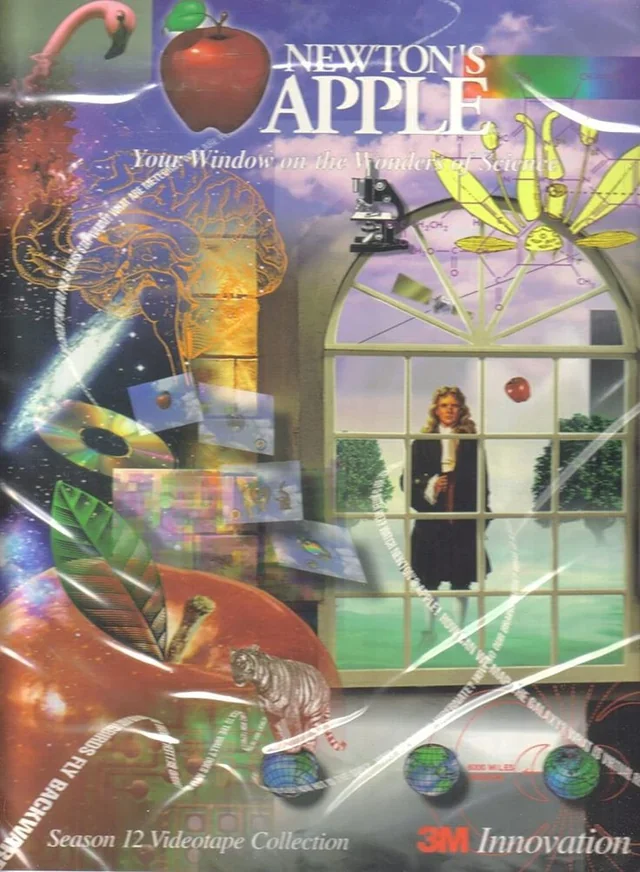

The educational print media products which featured Utopian Scholastic design include educational textbooks and encyclopedias (e.g., Dorling Kindersley (DK) Eyewitness Books beginning in 1988), atlases like DK Atlas of World History, (2000), classroom posters (e.g., NASA poster sets of “Our Solar System” and “Solar System and Beyond”), and related school curriculum materials. Dorling Kindersley (DK) is the leading publisher to implement the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic in print. Outside of the classroom, there were educational initiatives and public health campaigns aimed at the general public which employed the aesthetic such as the USDA Food Pyramid (1992). On TV, there were PBS children’s education programs such as Reading Rainbow (1983-2006) and Newton’s Apple (1983-1998) which displayed the aesthetic to attract the curiosity and wonder of young minds. There were other programs such as Disney’s Bill Nye the Science Guy (1993-1999) and A&E’s Ancient Mysteries (1994) which lend themselves to the aesthetic through the diversity of the topics covered. Educational companies such as The Museum Company Store – The Artifact (est. 1997) exhibited displays in their stores which typified the aesthetic. The digital media which employed the aesthetic is studied further below.

Design Principles

The look of Utopian Scholastic is both encyclopedic and structured on the one hand, and awe-inspiring on the other through its diverse, juxtaposed, and striking images which are arranged as an art collage. The viewer's first contact with the aesthetic is the juxtaposed and striking images of a collage to draw the viewer in with curiosity and wonder. Inside the product, like a book, there is a structured ordering of knowledge. Think of the clean crisp layouts with white backgrounds and wide marginal spaces of encyclopedias as exemplified by the Dorling Kindersley (DK) Eyewitness Books. These books employ white backgrounds and bright vivid chromatic colors in order to make the scientific diagrams, infographics, and other educational content, which sets within certain categories and hierarchies, are made memorable in a magical way. These design choices are not only meant to be visually appealing but memorable and engaging with the educational material; with technological advancements, interactive multimedia became a popular way to engage its audience.

Is Utopian Scholastic truly a unique aesthetic? Doesn't any kind of visual art form which communicates educational content dictate these very design principles which define it?

In contrast to this ordered knowledge is the design layout of art collages which produce sharp contrasts through juxtapositions of striking images against white backgrounds which make them memorable. Additionally, the aesthetic also employs a mixture of fonts giving it a museum exhibit-style feel. The aesthetic gives the impression as if a patron is walking through a museum and seeing all the extraordinary displays. The use of early CGI, 3D models, and 3D mapping offered the PC user an opportunity to navigate these utopian and surreal landscapes. What may seem like playful digital experiments like the point-and-click adventure games like Myst (1993), Labyrinth of Time (1993) and TimeLapse (1996) actually echoed mnemonic techniques first developed in classical antiquity. In edutainment, there is the DK Eyewitness Virtual Reality series (1996-2000) which produced educational content about dinosaurs, cats, birds, and geology through the same point-and-click adventure genre. The DK Eyewitness Virtual Reality series had a spectacular television intro in which the viewer moves through a museum-like building filled with all kinds of creatures from bird to dinosaurs which felt like an exciting adventure. The juxtaposition of the Utopian Scholastic’s design style can be anachronistic with historical images such as King Tut’s ornamental mask next to a NASA space shuttle; such juxtaposition gives a sense of timelessness. When historical images are juxtaposed to another, it creates a sense of timelessness and the eternity of ideas and deeper truths expressed through symbolism. In other words, the images symbolize certain kinds of truth and knowledge. In sum, the design principles of the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic are two-fold - on the one hand, it is an encyclopedic and ordered knowledge through structured composition and diagrams, and on the other hand, it presents striking images juxtaposed for sharp contrast against white backgrounds, symbolic imagery of ideas, and a directed navigation through utopian and surreal landscapes. Beneath the surface of the playful and didactic tone of the aesthetic, these design principles conceal the classical art of memory.

Roots in Memory Arts & Philosophy

The Classical Art of Memory

The art of memory (Latin: ars memoriae) is a system of techniques originating in classical antiquity and refined through the Middle Ages and Renaissance to help people to remember large amounts of information. The method of places, or the method of loci, is the crown jewel of the mnemonic arts. The practice incorporates other techniques which are hinted at in Utopian Scholastic – striking images (imagines agentes) in which a symbol represents a concept, fact, or truth, phonetic and verbal mnemonics through wordplay and poetic meter, and mental associations (similarity, contrast, and contiguity) made through the juxtaposition of the striking images.

The method of places requires the participant to choose a familiar place like a building, place of worship, or street. The familiar place is what is known. The desired and new information is converted into a mental image through a process called “imprinting” (e.g., a screaming fish rocketed upward on a jet of steam to symbolize the stage of evaporation in the water cycle). Next, mental images are stored at key locations within the familiar place (e.g., doorways, windows, stairs, corners, etc.). In this way, what is known (i.e., the familiar place) is united with what is unknown and new (e.g., the desired information such as the evaporation stage in the water cycle). Lastly, there is an ordered route which the participant does a mental walkthrough this imaginary landscape, passing by each key location where a striking image is anchored. In doing so, the participant recalls the information for which each image represents. In sum, there are three basic steps to the method of places: (1) imprint, (2) store, and (3) recall. The other mnemonic techniques help with this process. There is the art of how to visualize striking images such that its being was so vivid, bizarre, emotional, exaggerated, or grotesque that it is unforgettable (Rhetorica ad Herennium, book 3). The mnemonic technique works best when all the physical senses – sight, scent, smell, touch, and taste – are engaged with the mental image. The classical art recommends that these striking images be placed in a well-lit and plain background for optimal imprinting and memory recall. The ordered route through the familiar place is essential for memory recall; the participant can travel forwards or backwards but never out of order to the key landmarks. This stage of memory recall is reflected in the visual presentation of ordered knowledge in the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic.

The Utopian Scholastic aesthetic follows the mnemonic principle of spatial organization both for structuring education information and decorative motifs. Structuring information depends upon the medium. For example, an education textbook presents an appealing composition of a photo spread. Architectural features, while often appearing as decorative motifs in the aesthetic, echo the classical mnemonic tradition as memory aids in ordering and organizing the striking images in strategic locations along a pathway. For ornamentation, this echoing of the ancient tradition is expressed through modular grids, tessellations, checkered floors, and other geometric patterns (e.g., checkered floors are seen in Microsoft’s Encarta Mindmaze, an edutainment game within the multimedia program made available on CD-ROM). Moreover, layered compositions and high-contrast colors engage not only the memory but also the imagination which awakens excitement, surprise, and inspirational wonder.

Caption: Here are a series of images from the navigator of Packard Bell which shows the viewer who is able to move about his home to look at icons which represent different applications. The ability to move about a 3D model reflects the mnemonic technique of a visualized route in order to observe symbols which represent certain kinds of information. The checkered floor is found in Microsoft Encarta's Mindmaze, an edutainment game for kids, which represents structure and rooms which the player passes. The menu of Microsoft's Encyclopedia of Nature is orderly and visually rich with a variety of symbols.

In conclusion, the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic presents an ordered route through a space or building passing by striking images as evidenced in the intro to education programs (e.g., the DK Eyewitness, 1994-1997, and the Great Courses doing business as the Teaching Company). These journeys felt like an adventure of exploration which built a progressive narrative chronicling the participant’s personal discoveries and acquired knowledge. Thus, the visual motifs of labyrinths, mazes, and architectural fantasy even where the mathematical order meets the absurd and impossible, makes the content surprisingly unexpected and all the more memorable.

If the artwork does not educate, is it just some other art form?

In this way, the aesthetic shows historical precursors both in its design style and association with the art of memory. The Utopian Scholastic aesthetic echoes the mathematical precision, perspective, and symbolism of the German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer (1471 – 1528). During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the art of memory was explored through geometric and orderly figures such as found in the thirteenth-century treatise of angelic magic the Ars Notoria (see my translation and commentary here: About the Ars Notoria | Matthias Castle), the mnemonic wheel called the Art of the Mallorcan philosopher Ramon Llull (c. 1232 – 1316), and the complex mnemonic system of the Italian philosopher Giorando Bruno (1548 – 1600). In this way, the navigation of these utopian landscapes shows that the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic is kindred to other visual art forms such as Mathematical Art, Op Art, (e.g., M.C. Escher whose art is a hybrid of the mathematical and the optical illusions; Minoru Nomata), Capriccio (e.g., Giovanni Paolo Panini, Viviano Codazzi), and Surrealism (e.g., Salvador Dali). All these mnemonic principles align well with the pedagogical purpose of teachers and educators who utilize media products to instruct their students. In summary, Utopian Scholastic is a modern, playful, and visually optimistic reinterpretation of the classical art of memory.

Neoplatonic Philosophy

From a philosophical perspective, the design principles of the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic subtly touch on the metaphysics of Neoplatonic thought, sharing deep structural affinities. This explains why those DK Encyclopedias looked so magical and awe-inspiring. They are a visual feast that leads one into deep contemplation. Utopian Scholastic visualizes Neoplatonism by transforming its abstract and metaphysical concepts of emanation, unity, hierarchy, and imaginal ascent into a vibrant, modern, and playful aesthetic. According to Neoplatonism, all reality flows from "the One", descending through Nous (The Intellect) and Psyche (The Soul) to the material world. In parallel, Utopian Scholastic arranges knowledge in a hierarchical or cascading manner through diagrams, charts, and layered systems of thought from abstract principles down to concrete details. Neoplatonism describes "the One" as the absolute unity from which the multiplicity of things emerges through emanation. Similarly, the aesthetic strives to bring multiple things into a unified visual structure through complex branching tree diagrams and encyclopedic systems of thought. All things connect and return to "the One" in Neoplatonism, and likewise, all diverse details are contained, nested, and interconnected by an overarching principle or single concept. In Neoplatonism, between the Nous (The Intellect) and the material world lies the imaginal realm where symbols are the means through which the Neoplatonist ascends back towards unity through ritual, prayer, and meditation. In Utopian Scholastic, symbols, allegories, and visual metaphors are vehicles for thought. In this way, symbols are bridges between the abstract and the concrete such that learning is framed as a ladder of ascent towards higher understanding, both intellectually and spiritually. According to Neoplatonism, beauty is an expression of the divine signature through symmetry and geometric proportion. In parallel, Utopian Scholastic emphasizes symmetry, proportion, ornamentation, and interconnectedness through diagrams and architecture, affirming beauty as a unifying and structuring principle. Knowledge is cumulative with each level or tier of scholarship is visible and accessible, making the aesthetic feel both familiar and uncanny. Neoplatonism claims there are higher truths hidden from the uninitiated and only through allegory and layered meanings are cosmic mysteries revealed. Utopian Scholastic expresses a self-aware irony that its excessive order and maximalism hint that behind the diagrams lies the ineffable and uncontainable. Both employ a playful concealment through symbolic imagery and correspondences gesturing towards truths which lie beyond literal grasp. For the Neoplatonist, "the One" lies beyond rational thought. In the end, both Neoplatonism and the design principles governing the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic are positive and life-affirming in the pursuit of knowledge and truth.

Cultural Context

The Utopian Scholastic aesthetic derives its emotive from two parts – the design style and cultural forces from which it arose. The design styles of the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic evoke a sense of wonder, discovery, and intellectual curiosity about scholastic knowledge. Certain cultural forces bestowed the aesthetic’s optimism and hope for a brighter future. It is these same cultural forces which evoke nostalgia in the older adults who lived through the heyday of the aesthetic. This section of the article explores those cultural forces which offered that sense of optimism in the aesthetic. The driving cultural forces which propelled the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic into mainstream and corporate culture include the following:

· The end of political struggles and injustice

· Rapid advances in technology

· Relative global economic growth

· The second wave of environmentalism

· Advances in astronomy, space exploration, and deep-sea exploration

· The symbolic significance of the dawning of the New Millennium

The End of Political Struggles and Injustice

Following the historic dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev’s reformation policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) reverberated throughout the world, encouraging open discourse and democratic tendencies which were welcomed in the West. The dissolution of political and social barriers in Germany and the Soviet Union gave hope on a global scale for unity, cooperation, and cross-cultural exchange. There was a sense that humanity could progress through shared knowledge.

After the Gulf War (1990-1991) and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States emerged as the undisputed and leading superpower of the world. The United States gained military confidence in its decisive victory in the Gulf War, redeeming itself after the painful defeat of the Vietnam War (1954-1975). The war coincided with a period of U.S. technological and economic dynamism, fueling the optimistic belief that America would dominate in the New Millenium.

In 1994, an important chapter in history was closed on the institutionalized racial segregation in South Africa and South West Africa known as apartheid. The practice sparked significant international opposition, resulting in one of the most influential global social movements of the 20th century. The first elected president of South Africa Nelson Mandela (1918 – 2013) became a symbol of peace and hope for social progress following his legacy of dismantling apartheid by fostering racial reconciliation.

These three major historical events share the cultural themes of American optimism and confidence at home, and they cultivated the belief that America could lead the globe through cooperation for peace and justice. This optimistic atmosphere was palpable in the streets and homes in America, but it is the workplace where its artistic expression was made using new technologies.

The Information Superhighway

Technological advances were bringing information and communication to people on an unpreceded scale, ushering in a new era of connectivity. The most important was the rise of the Internet and World Wide Web, personal computers (PCs), operating systems, portable digital media (e.g., CD-ROMs and multimedia) and PC games. These technologies were leveraged in the production of the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic. This included desktop publishing software, which utilized stock photography collections, and creative minds made innovations with early computer-generated imagery (CGI) and 3D models like those used in the 1993 blockbuster movie Jurassic Park. In addition, edutainment software boomed with the point-and-click adventure game Myst (1993) and MECC’s Oregon Trail (1971). Originally a text-based game, Oregon Trail was re-imagined in 1985 for an immersive experience for the player which saw eight more versions of the computer game during the era of Utopian Scholastic. Digital exemplars of the aesthetic include the Microsoft’s Encarta (1993-2009), the popular multimedia encyclopedia, The life simulation video game franchise Sim City 2000 (1993) and Sim Meier’s Civilization (1993) gave players the opportunity to create their own utopian ideal. David Macaulay’s children’s educational book The Way Things Work (1988) saw a Dorling Kindersley interactive CD-ROM in the 1990s. The digital medium was designed to be interactive, immersive, story-driven, and educational. Recall that early CGI, 3D models, and 3D mapping offered the PC user an opportunity to navigate these utopian and surreal landscapes through point-and-click adventure games and edutainment software. Digital media reshaped the aesthetic through deeper immersion and interaction than what print media could do.

The 1990s Boom and Dawn of the New Millennium

The United States experienced its longest period of sustained economic expansion in history from 1991-2001. There was low inflation, low unemployment, and rising productivity created widespread confidence. The dot-com boom inflated stock markets, which quadrupled between 1995 and 2000. Household wealth grew, and many felt that the middle class was expanding. People felt confident about the relative global economic growth of the 1990s; they believed an era of prosperity, interconnected markets, and technology-driven progress would usher in the New Millennium. Suze Huldt defines the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic as an “end-of-history” perspective, linking it directly to Francis Fukuyama's book entitled The End of History and the Last Man (1992). Fukuyama argues that the rise of Western liberal democracy marks a significant endpoint of human history. This was a time when the globe was looking forward to the future and the New Millennium, which for some, offered a feeling of starting fresh and "wiping clean the slate" for new beginnings, while others suffered from anxiety about the future as typified in the Y2K bug.

“Think Globally, Act Locally”

The second wave of environmentalism (late 1970s-1980s, into the 1990s) broadened the scope of environmental concerns about pollution to global ecological issues such as ozone depletion, deforestation of the tropical rainforests, biodiversity loss, and a growing attention to climate change. For the youth, the target audience of Utopian Scholastic, there were School Earth Day celebrations which involved tree planting, clean-ups, and poster campaigns. There were youth-focused campaigns by non-governmental organizations like World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), Greenpeace, and Friends of the Earth. At the Rio Earth Summit (1992), non-government organizations (NGOs) created youth posters, films, and guides (e.g., Rescue Mission: Planet Earth, a children’s edition of Agenda 21).

There were also public TV programs promoting the environmentalist’s agenda. There was PBS’s 3-2-1- Contact which had ecological segments (e.g., Earth is Change - Erosion) paired with scientific diagrams with upbeat and idealistic messages. The BBC’s Tomorrow’s World explored eco-technology with an aesthetic of optimistic futurism. The youth-targeted environmental media delivered a message of utopian hope that the Earth was knowable, manageable, and savable through knowledge and cooperation. While the message was educational and optimistic, it did not always fit the Utopian Scholastic as defined above. Indeed, the second wave of environmentalism and the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic may be two forces running in parallel and intersected with one another in far fewer instances than many are willing to admit. Yet, there was the Discovery Channel and The Learning Channel (TLC) who produced marketing materials which sometimes illustrated the aesthetic.

Natural history museums presented displays in their gift shops which sometimes embodied the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic during the second wave of environmentalism. Indeed, many companies were founded during this era to capitalize upon the environmental movement. There was the retail chain The Nature Company (1972-2001) whose catalog mirrored the aesthetic, selling nature-themed items such as rain sticks, nature sounds on CDs, telescopes, and scientific toys. Other educational digital media with an environmental theme sold at this time included SimEarth: The Living Planet (1990), Microsoft’s Dangerous Creatures (1994), and Microsoft’s Explorapedia: The World of Nature (1994). Nature-themed aesthetics for product design naturally lends itself to a diversity of visually striking images through biodiversity. Question: Does the biodiversity of nature make for a perfect fit with the design principles of the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic which makes striking juxtaposed images? Does a plethora of animals on a CD album mean it carries the signature of the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic or is it something else?

The Rainforest Craze

The jungle-themed restaurant chain Rainforest Café (founded 1994) belongs to a niche within the environmental agenda which became known as the Rainforest Craze of the 1990s. The craze had remarkable traction in which the rainforest was successfully tied to urgent conservation messages, and the belief that its mysterious plant species may hold a cure for life-threatening diseases such as cancer. This belief was portrayed in the 1992 film Medicine Man starring Sean Connery and Lorraine Bracco. Although Jurassic Park (1993) was primarily about dinosaurs, there were scenes which featured the lush tropical jungle, giving it an aura of mystery and danger of “untouched” ecosystems. Non-governmental organizations like Rainforest Action Network and National Geographic brought the exotic images and stories of the Amazon to American homes. Celebrities like the English musician Sting (b. 1951) through his Rainforest Foundation (1989) and Leonardo DiCaprio through his namesake foundation (1998) helped popularize “rainforest consciousness”. The rise of the commercialization of “world music” incorporated rainforest sounds, and aesthetics as found at The Nature Company. In short, the Rainforest Craze manifested through popular media to symbolize the rainforest as an endangered, mysterious, and exotic place of adventure combined with ecological consciousness and ethical consumerism. The Rainforest Craze was both aesthetic and moral: it provided exotic imagery for entertainment while also giving Americans a tangible way to connect and feel responsible for global ecological issues through purchasing decisions and environmental activism. Lastly, the non-governmental organizations pictured the rainforest as one of the last frontiers, which is part of one of the great cultural attitudes of the 1990s optimism, that America can lead the world into the frontiers of space exploration and deep-sea exploration.

Exploring the Frontiers: The Ocean

The public fascination with frontiers – the rainforest, the ocean, outer space, and the future – were pervasive during the 1990s. Deep sea exploration took the national spotlight through scientific news about technological advances such as submersibles, underwater robotics, and sonar mapping. In 1985, Robert Ballard discovered the Titanic wreck which made the idea of deep ocean exploration feasible. In 1986, real-world environmental debates inspired the collision of both frontiers – outer space and the ocean – in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home which brought public awareness about the endangerment of humpback whales to the silver screen. The environmental movement portrayed the ocean as both mysterious and fragile. Scientific news stories inspired Hollywood in the production of James Cameron’s sci-fi movie The Abyss (1989) and the sci-fi TV series SeaQuest DSV (1993-1996). SeaQuest DSV marketed itself to families and schools, working to position itself as both entertaining and educational, much like the edutainment wave at the time. In the early 1990s, virtual reality as a form of entertainment was entering popular culture through science museums. The company Iwerks Entertainment with Evans & Sutherland, the originators of virtual reality, developed an edutainment family attraction game called Virtual Adventures: The Loch Ness Expedition (1993). This was a 24-player game which consisted of four teams with six players each. Each team took on the imaginary role as “volunteer scientists” who were sent on a deep-sea mission in a submersible to rescue Nessie’s eggs from bounty hunters and other deep-sea creatures. Each player had a unique role in the submersible such as operating the mechanical arms which could grab the egg, the pilot of the submersible, and the commander who navigated the underwater terrain. This is an excellent example of how the public’s fascination with deep-sea exploration and the advanced technology of virtual reality submerges into the creative waters of edutainment at a maritime science museum creating a truly Utopian Scholastic experience! (Celia Pearce & Friends, [ISEA94] Artists Statement: Iwerks Corporation – Virtual Ad Ventures (1993) | ISEA Symposium Archives). Each medium – print, digital, TV, virtual reality – dictates how the message is conveyed. Do these embody the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic?

Exploring the Frontiers: Outer Space

The 1990s was a golden decade for astronomy in which new space technology, sharper telescopes, and fresh theoretical breakthroughs were happening. In 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope launched aboard Space Shuttle Discovery. When its optics were fixed in 1993, the telescope gave humanity some of the sharpest images of the cosmos to date. The Hubble Deep Field (1995 & 1998) images showed thousands of galaxies in a seemingly empty patch of sky, revolutionizing ideas about galaxy formation. In fact, these very images became aesthetic icons imprinted upon the young minds learning about them through Utopian Scholastic edutainment products such as Where in Space is Carmen Sandiego? (1993). (The Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? edutainment franchise about learning geography and was wildly popular spawning multiple forms of media – games, films, TV shows, animated series, and more.). In 1994, the Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 impacted Jupiter, being the first observed collision between two bodies in the solar system. In 1995, the first exoplanet around a Sun-like star was discovered which shattered previous assumptions about planetary systems. Planetary missions with spacecrafts were launched to Mars, Saturn, and the Jupiterian moon Europa. In 1998, scientists discovered the accelerating expansion of the universe, implying the existence of dark energy. These discoveries and space missions reinforced public optimism about possible futures amongst the stars, and they appeal to Utopian Scholastic’s sense of wonder, adventure, and mystery in which visual and astronomical data is depicted with aspirational futurism, cosmic harmony, and educational universality. Another example of the aesthetic is The Magic School Bus series, and the authors, Joanna Cole and Bruce Degen, even had one for astronomy called The Magic School Bus Lost in the Solar System (1992).

Is Utopian Scholastic just for 90s kids, or can it be for grown-ups today?

Decline and Revival

Utopian Scholastic was replaced by the clear and simple aesthetic called Frutigero Aero in the 21st century, but this was temporary. Utopian Scholastic was rediscovered in 2017 and has been experiencing a revival on the Internet. There is growing archival collection of its nostalgic images by Evan Collins, and the atmospheric feel of the aesthetic is reinterpreted through its own music genre called Utopian Virtual, a microgenre of Vaporwave which is classed within electronic music. The music is playful and uplifting, and it is characterized by synths, atmospheric and ethereal melodies seeking to evoke that child-like wonder of learning. For those young children who grew up with the 1990s aesthetic now experience its musical compositions as a form of escapism, nostalgia, and tranquility. Two notable musicians are Daniel White (2019 – present) and Trndytrndy (2024 - present) on Bandcamp. Those who are rediscovering Utopian Scholastic are struck by its nostalgia and its zeitgeist of optimism. Today, some struggle to define its boundaries. It is my hope that mapping out the design principles and the milieu from which the aesthetic arose will help readers to consider and question its definition and boundaries. The design style shows roots in the classical art of memory and Neoplatonism which evokes its sense of wonder and intellectual curiosity through striking and juxtaposed images and adventuring through labyrinthine routes in imaginary landscapes and architecture. There were multiple forces converging in the 1990s – political, economic, technological, and cultural – that boosted American society’s optimism and confidence about the future. In short, the Utopian Scholastic aesthetic embodied ordered knowledge as wonderous journeys and narratives for young minds to explore during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Will the revival of Utopian Scholastic be able to recapture and carry on that wonder and optimism again?

Written by Matthias Castle

None of these copyrighted images are mine; they belong to their respective owners. If you own the copyright to any of these images and would like me to remove it, then you may email me, and I will do so. This article is for educational purposes only.