The Scope of Western Palmistry: Historiography, Canon, and Transmission

- Matthias Castle

- Jan 26

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 27

This article is part of the Divination Hub.

Introduction

Modern representations of palmistry are largely shaped by the nineteenth-century French tradition and its later Victorian and American adaptations, which emphasized character analysis and so-called “scientific” methods of interpretation. These modern systems have come to dominate popular understandings of palmistry and have obscured its historical origins and intellectual complexity. They project contemporary assumptions backward onto premodern sources and give the false impression that the French symbolic system exhausts the field.

Historically, Western palmistry—known in earlier periods as chiromancy—did not originate in France but emerged from ancient Greek traditions that were transformed through Arabic intermediaries and later incorporated into medieval and Renaissance European intellectual culture. From the Middle Ages through the early Italian Renaissance, chiromancy developed as a symbolic system embedded within medicine, astrology, physiognomy, and natural philosophy. Its earliest texts were compilations assembled from earlier authorities and frequently attributed pseudonymously to prestigious figures such as Hermes Trismegistus and Aristotle. These works were reorganized according to pedagogical and practical needs rather than theoretical originality.

Although the manuscript tradition displays variation and scribal conflation, a coherent symbolic grammar persisted for centuries. This older chiromantic system was eventually eclipsed by the nineteenth-century French occult revival, which reshaped palmistry into a new form that now dominates modern practice.

To study Western palmistry historically is therefore not to evaluate the truth or falsity of its claims, but to analyze the intellectual frameworks through which premodern authors interpreted signs of the hand as indicators of temperament, health, character, and fate. This essay situates Western palmistry within its historiographical context, defines its cultural boundaries, and outlines the scope of its principal textual and intellectual traditions.

Defining “Western Palmistry”

By “Western palmistry,” historically termed chiromancy, this essay refers to traditions transmitted through:

Greek sources and their Arabic Muslim and European Christian intermediaries (including Aristotle, the Pseudo-Aristotelian corpus, and the Pseudo-Aristotelian Hermetica).

Latin medieval and Renaissance texts circulating in Europe, including works in Italian, German, French, and English that together formed an unspoken canon of chiromantic literature.

Early modern codifications of this canon, such as those of Jean Taisnier, Rodolphus Goclenius the Younger, and Nicolas Pompeius.

The nineteenth-century French tradition of Casimir Stanislas d’Arpentigny and Adrien Adolphe Desbarrolles, which reshaped palmistry and exported it to the English-speaking world.

This definition excludes independent traditions such as Indian hasta samudrika and Chinese hand divination, which developed within distinct cosmological and medical systems. Western palmistry thus shares its transmission history with Western astrology and Western medicine: Greek foundations, Arabic elaboration, Latin scholastic integration, early modern codification, and nineteenth-century occult revivalism followed by modern scientization.

Historiographical Context

Modern discourse on palmistry is polarized between popular occult revivalism and skeptical dismissal. The former treats palmistry as a perennial and universal divinatory art, while the latter reduces it to superstition or pseudoscience. Both positions obscure its historical embeddedness within learned traditions of natural knowledge.

Over the past century, historians of science and religion have demonstrated that astrology, physiognomy, and divination formed integral parts of medieval and Renaissance intellectual culture. Lynn Thorndike established that practices now labeled “occult” were once continuous with medicine and natural philosophy. Charles Burnett and his collaborators have shown that divinatory and physiognomic texts were transmitted through Greek and Arabic intermediaries and integrated into Latin scholastic contexts. Monica Azzolini has demonstrated the institutional legitimacy of prognostic arts in Renaissance courts, and Wouter Hanegraaff has framed such traditions as part of the history of “rejected knowledge,” emphasizing the modern construction of boundaries between science and esotericism.

Palmistry belongs within this historiographical trajectory. It must be understood as part of a broader semiotics of the body, alongside physiognomy and metoposcopy, rather than as an isolated curiosity.

The Forgotten Canon of Western Palmistry

Western palmistry rests upon a corpus of medieval and early Renaissance source texts—often anonymous—that articulate a consistent symbolic system grounded in astrology and natural philosophy. These texts presuppose a cosmological narrative in which the soul passes through the celestial spheres and is impressed by planetary influences. Upon incarnation, these influences manifest as sensible signs on the physical hand.

Chiromancy was therefore conceived as a natural science: the hand functioned as a readable surface upon which cosmic causation became visible. Through a semiotic logic of correspondences, practitioners interpreted lines, shapes, and markings as indicators of character, health, morality, and destiny.

For centuries, this symbolic grammar formed the unspoken canon of Western palmistry. Although transmitted through compilations and subject to scribal variation, its underlying cosmological structure remained stable. Only in the nineteenth century did this older canon become overshadowed by the French occult revival.

The scope of Western palmistry thus encompasses not only its textual traditions but also its associated intellectual frameworks: Western astrology, Galenic medicine, Greco-Arabic physiognomy, and medieval Islamic medical theory. It also intersects with Hermeticism, the Pseudo-Aristotelian Hermetica, Neo-Hermetic Kabbalah, and related divinatory practices such as metoposcopy.

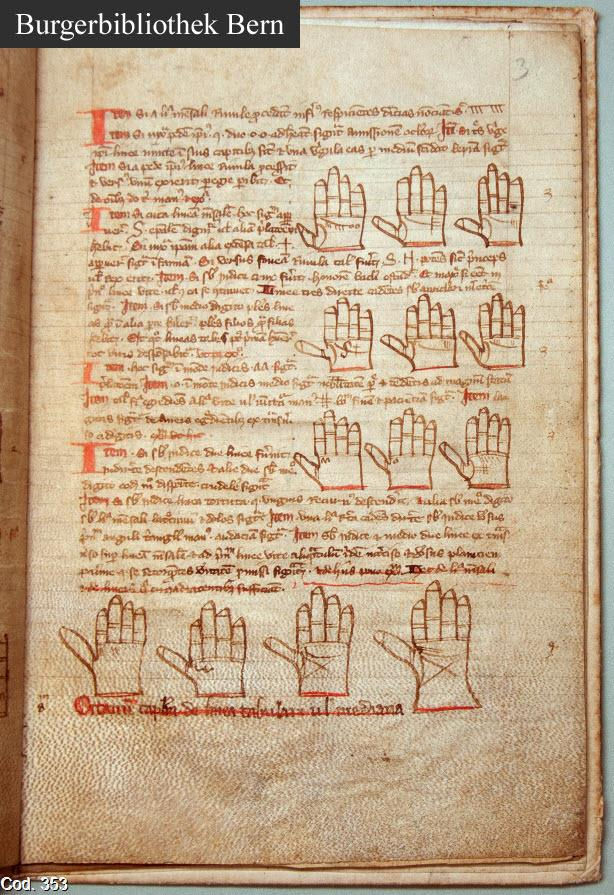

Compilation and Transmission

A defining feature of Western palmistry is its textual form. Most surviving works are compilations: lists of signs, schematic hand diagrams, and collections of prognostications assembled from earlier authorities. Rarely do they present unified theoretical treatises. Instead, they juxtapose humoral medicine, astrology, physiognomy, and symbolism within single manuscripts. While Western palmistry resists a single doctrinal system, it exhibits a consistent symbolic grammar rooted in astrological cosmology and humoral theory. Despite scribal conflations and transmission errors, the continuity of this grammar across centuries indicates a stable interpretive tradition rather than a series of disconnected practices.

Ecclesiastical Condemnation and Cultural Transformation

Western palmistry also encountered sustained criticism from the Church, premodern scientists, skeptics, and detractors. Once such detractor was the German Christian Johannes Hartlieb (c. 1400–1468), who, in his Book of All Forbidden Arts (1456), condemned chiromancy alongside necromancy, geomancy, hydromancy, aeromancy, pyromancy, and spatulamancy. Such condemnations reveal the perceived theological and moral risks of bodily divination within Christian Europe. Yet, despite these kinds of oppositions, chiromancy persisted through the Early Modern period and underwent its codification. However, the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment undermined the cosmological worldview that sustained its symbolic system. In response, chiromancy, or palmistry as it was increasingly being called, was transformed rather than abandoned.

The Nineteenth-Century French Reconfiguration

In the nineteenth century, palmistry reemerged in France in radically altered form. Casimir Stanislas d’Arpentigny developed a neo-physiognomy of the hand, which he called chirognomy. He classified seven hand types—elementary, spatulate, conic, square, knotty, pointed, and composite—and reframed palmistry as character analysis rather than cosmological divination.

Adrien Adolphe Desbarrolles harmonized older chiromantic doctrines with contemporary occult currents, including Neo-Hermetic Kabbalah, phrenology, and graphology. He termed this synthesis chiromancie nouvelle. Through translation and popularization, this French system entered the English-speaking world and became the dominant modern form of palmistry.

Subsequently, palmistry adopted new names—chirology and chirosophy—and aligned itself with characterology, popular psychology, and New Thought. In the twentieth century, it further incorporated elements of dermatoglyphics and congenital hand disorders, lending it a false but modern scientific veneer. This transformation displaced the older medieval canon and reshaped palmistry into a system oriented toward personality analysis rather than cosmological interpretation.

Implications for Study

Recognizing the scope of Western palmistry has several methodological consequences:

It prevents anachronism by distinguishing historical chiromancy from modern commercial practices. This is especially true for the lenses of astrology, physiognomy, and medicine which had to reconfigure themselves following the Scientific Revolution and new discoveries as their technical terms shifted in meaning and certain ideas became obsolete.

It situates palmistry within the history of medicine and natural philosophy rather than outside intellectual history. Palmistry as a symbolic system relies upon layered correspondences of symbolic meaning for its depth and breadth of meaning and interpretations.

It reveals palmistry as part of a larger tradition of bodily semiotics shared with astrology and physiognomy.

It underscores the importance of manuscript study and source criticism over reliance on later printed manuals. Modern palmistry's divorce from its historical roots expresses a hidden embarrassment of its premodern origins.

Western palmistry thus emerges not as fringe superstition but as a historically coherent attempt to interpret the human body as a meaningful text within a structured cosmology.

Conclusion

Western palmistry should be understood not as a singular method of fortune-telling but as a complex family of interpretive practices rooted in Greek, Arabic, and Latin intellectual traditions. It participated in medicine, astrology, and physiognomy and was shaped by the compilation culture of medieval scholarship. Its symbolic grammar endured for centuries before being transformed by the nineteenth-century French occult revival and later scientific reinterpretations. To study palmistry historically is to study how premodern thinkers believed the body signified health, character, and destiny. Its scope is therefore far broader—and far more intellectually serious—than modern stereotypes allow.

Appendix: The Diverse Traditions of Palmistry

The Vestiges of the Greek Tradition

(Late Antiquity - Late Middle Ages; dating likely uncertain and contested)

• The Greek Fragment, or The Prognostic Lines of the Palm (14th – 15th c., preserved in seven mss., Franz Boll (1908), Roger A. Pack (1972), and Alberto Bardi (2017, 2022)

• The Martial Fragment (Gerolamo Cardano, De Rerum Varietate, 1558, 15.79.718)

• The cheiroscopic treatise according to Helenus of Troy (there is a late recension which survives in Latin, this version is newly named, Divinis Litteris, preserved in two witnesses, the Ex Divinia Philosophorum Academia and in the Anastasis of the Italian chiromancer Bartholomeus Cocles, both dated to 15th c.)

• The cheiroscopic treatise of Hermes Trismegistus (scattered fragments in Bartholomeus Cocles, Anastasis, 15th c.)

The Latin Tradition

Twelfth-Thirteenth Centuries

• The chiromantic treatise found in the Eadwine Psalter. Translated by Charles Burnett (1987, 1996).

• Dextra Viri, Sinistra Mulieris (Right Hand of a Man, Left Hand of a Woman), a plentiful manuscript tradition. Translated by Charles Burnett (1987, 1996).

• Chiromantia Parva (Little Chiromancy), 13th c. I have identified this text as having three versions which I call A, B, and C. Version A is the long version found in the manuscript shelf marked 7420A at the BnF in Paris. Version B is the short version as translated by Charles Burnett (1987, 1996). Version C is Liber Chiromantiae Incerto Autore in Antiochus Tibertus’ De Cheiromantia Libri III (A Book of Chiromancy by an Unknown Author in Antiochus Tibertus' On the Three Books of Chiromancy).

Fourteenth-Fifteenth Centuries

• The chiromantic treatise falsely attributed to Albert Magnus

• Master Rodrigeuz of Mallorca, Tractatus Ciromanciae

• Cyromancia Aristotilis Cum Figuris, 2 separate volumes, falsely attributed to Aristotle; the first treatise is comprised of 11 chapters; the second treatise is constituted of 3 principal parts. See Roger A. Pack and R. Hamilton.

• Fragmentum Cuiusdam Operis Chiromantiae (A Fragment of a Certain Chiromantic Work)

• The Secantur Fragment, named after the first word in its most commonly attested incipit, which I have renamed as A Proem on the Three Divisions of the Hand, is presserved in Cocles and several other mss.

• Bartholomeus Cocles, Anastasis. I have translated his Book 5: Chyromantia Magna (The Great Chiromancy), which is a chiromantic compilation attributed to Peter of Abano.

• John the Philosopher, Summa Chyromanciae (The Best of Chiromancy)

• Johannes de Indagine, Introductiones Apotelesmatics

• Antiochus Tibertus of Cesana, De Chiromantiae Tres Libri (1494)

• The Chiromantia of MS Sloane 323. Translated by Charles Burnett (1987, 1996).

• Andreus Corvus of Mirandola, Absolutissima Ratio Chyromantiae (The Most Absolute Rationale for Chiromancy, before 1504)

Italian Tradition

Fifteenth-Sixteenth Centuries

Andreas Corvus, Antiochus Tibertus of Cesana, Bartholomeus Cocles, Patritio Tricasso of Cerasara, Abramo Colorni, Redeolfo Coclenio, Gerolamo Cardano, Antonius Piciolus, and others.

German / Dutch Traditions

Fifteenth-Twentieth Centuries

Pseudo-Johannes Hartlieb’s Die Kunst Ciromantia (which contains the Fragmentum Cuiusdam Operis Chiromantiae), Magnus Hundt, Johannes de Indagine, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim, Jean Taisnier, Johannes Rothmann, Rodolphus Goclenius the Younger, Nicolas Pompeius, Johannes Praetorius of Zeitlingen, Philip Mey of Coburg, Johann Abraham Jacob Hoeping, Christoph Schultz, Johann Ingeber, Carl Gustav Carus, and others.

Anglo-Norman and French Tradition

Fourteenth-Nineteenth Centuries

Early translations of the Latin tradition, Rampalle, Marin Cureau de la Chambre, Jean Baptiste Belot, Casimir Stanislas d’Arpentigny, Adrien Adolphe Desbarrolles, Henri Mangin, Georges Muchery, and others.

English-Speaking Tradition

Fourteenth-Twentieth Centuries

The oldest Middle English palmistry tract found on the Digby Roll 4, John Metham of Norfolk, Fabian Wither’s 1558 English Translation of Johannes de Indagine, Robert Fludd, George Wharton’s 1652 English Translation of Johannes Rothmann, Richard Saunders, Edward Heron-Allen, Rosa Baughan, the Cheirological Society of Great Britain, Noel Jaquin, Beryl Butterworth Hutchinson, Terence Dukes, Ina Oxenford, Katharine St. Hill, Le Comte C. de Saint-Germain, William John “Cheiro” Warner (also named himself as Count Louis le Warner de Hamon), William G. Benham, Fred Gettings, Andrew Fitzherbert, Christopher Jones, and many others.

This digital edition by Matthias Castle, Copyright 2026. All rights reserved.

Please do not copy this text to your website, or for any purpose other than private use.

These images are either AI-generated or within the public domain.

Comments